“So, where are you thinking of giving birth then?”

This inevitable question is one that pregnant women hear time and time again. A question that often is the first one out of your GP’s mouth when your pregnancy is confirmed. It has become very apparent in today’s society, that the ‘where’ of birth is just as important as the ‘how’. Will you give birth at a private hospital? A public hospital? A birth centre? At your home? Outside? Inside? On a bed? In a bath? In the ocean? In the dark? Under lights? With music? Without music? There obviously is a numerous amount of choices available for birthing women. Because where you give birth, isn’t just about the physical space. It also is about what kinds of people, smells, sounds, sensations, mood and overall atmosphere you desire to have as part of your birth. It’s about how that space fits in with your birth plan, and whether it aligns with your beliefs and values around giving birth. Why is this important? Because the environment you give birth in impacts your experience and your birth experience matters. Your experience of birth, whether positive or negative, can stay with you for years after the actual event. It has the ability to change and transform you. Harm you or heal you. Empower you or disempower you. So, yes, the place you give birth in will affect your birth experience. Just as you would pick a house as your home, so too is the important decision to choose your birth space. But with all these different options out there, how do you actually make a decision? How do you know what type of space is right for you and your family?

One of the main comparisons that birthing women make, is whether to birth at a hospital or home. Each place has risks and benefits and positives and negatives. And each place will be more suited to one mother than the other. Birth is completely individualised. In fact, “there is no strong evidence from randomised trials to favour either planned hospital birth or planned home birth for low-risk pregnant women” according to a Cochrane review. That is why it is so important to do your research to find the best fit for you and your birth. Yes, birth can be unpredictable. But the research shows that a mother, who feels in control of her birth, will have a more positive experience. And what can you control? The place you choose to give birth in. Even if that choice has been taken away from you, such as in some high risk pregnancies, there are still things you can do to make your birth space truly yours.

According to the Australian Mothers and Babies 2017 report, “almost all births in Australia occur in hospitals.” In Western Australia alone, hospital birth accounts for 97.4% of all births in the state, with 3 in 4 mothers nationwide, choosing public hospitals over private. A hospital is defined as “an institution providing medical and surgical treatment and nursing care for sick of injured people” therefore a hospital birth is a birth that has taken place in a “patient centred” space. Up until the early decades of the twentieth century, women from Western cultures mostly birthed at home, under the care of highly experienced yet unregistered midwives. Home birth at this time was a mixed bag of risks and benefits. Women were cared for by midwives who were highly experienced and skilled in their ancient craft, yet women and babies that died during childbirth were seen as the norm. Low income, poor sanitation and general lack of health and medical understanding, made childbirth an accepted danger in society. During the 1830’s doctors were sometimes called in to help midwives with a difficult birth. Unfortunately, “doctors were often the unwitting sources of infection.”

Transmission of disease was high and despite the doctor’s best efforts, lack of medical knowledge and training meant haemorrhage and death was common place. However, by the second world war, things begun to improve with “the development of antibiotics [which] meant that the scourge of postnatal fever was no longer so terrifying, [and] hospital wards did not have to be places of doom.” By the 1950’s, hospital birth was becoming the new norm, with increased training and registration for doctors and midwives. Hospital wards were “run like the army” with things as enemas and pubic shaving routinely performed on mothers when they arrived. This shift from home to hospital also brought on a change in hierarchy, with midwives now working for the obstetricians, and hospitals becoming highly patriarchal. The idea of the birthing woman as a machine became more apparent “with the function of delivering the final product, the baby.” By the 1960’s, pioneers of fear-free childbirth like Fernard Lamaze and Grantly Dick Read, were revolutionising how women and society viewed birth, pushing for birth education to become standard practice. Popularity of relaxation techniques and maternity wards that looked less clinical and more “homely” started to rise. Despite this, hospitals still have far to come if they are to be compared to the familiarity and hormone inducing benefits of a home birth.

In today’s world “maternity care is now so entrenched in the hospital medical system that it is hard to believe that pregnancy was ever regarded as anything other than a medical condition that requires a hospital and a doctor”6. Hospital birth is the norm for many reasons: because society perceives it as the safest option, because women have access to medicalised pain relief such as an epidural, and that modernised technologies like continuous foetal monitoring are usually only available in a hospital setting. The idea that the obstetrician is the leader in the birth room because they can perform life-saving surgeries (i.e. caesarean section), also accounts for mothers’ choice to birth at hospital. Despite hospitals often having “a lack of privacy and peace, and a greater risk of obstetric intervention…for many women, the advantages of hospital birth outweigh the disadvantages.”

My own experience with hospital birth is mixed. As a doula, I see a hospital as exposing mothers to unnecessary medical interventions and a general lack of respect or patience for physiological birth. As a mother, I see a hospital as the place that saved my life from a severe and potentially life threatening postpartum haemorrhage, soon after the birth of my daughter. Without the quick and skilled work of the midwives, surgeon and nurses in hospital, my husband may have been left a single dad and my daughter motherless. So in this way, I am incredibly thankful for the help that hospitals can provide. However, I believe the lines of safety and true risk have been blurred in birth, with many mothers having “appalling experiences of contemporary maternity care”. Often the “general consensus among obstetricians [is] that the physical safety of mother and baby [is] the primary goal” and therefore women’s voices in hospital are rarely heard and their birth preferences overridden. Hospitals are sometimes perceived as cold places, focused on routine and policy rather than empathy and support. But on the other hand, hospitals are clean, safe and highly skilled places that are well equipped to handle high risk situations. It really is all a matter of perception and individual experience.

When discussing birth with other mothers, it was obvious that each experience is unique to the individual. Kirryn Simpson, a Perth mother, describes her hospital birth as “enjoyable and safe”. Whereas a mother from Victoria, (who I will refer to as Mama A) told me she “didn’t find hospitals a calming place”, despite being a midwife herself and ultimately giving birth at the same hospital she worked at. Both mothers had their first birth in hospital and then went on to choose a home birth for their second. Both admitted that choosing to birth at a hospital was influenced by ‘first-time-mum’ inexperience and naivety, with Mama A stating she just “went with what [she] thought was the norm at the time”. Often many mothers find themselves doing what is first suggested by their GP, as many don’t realise the benefit of research and the options available. In Kirryn’s situation, following her IVF pregnancy, her GP referred her to the Midwifery Group Practice at her local hospital. Due to the IVF, the hospital viewed Kirryn as high risk, which meant she had to see an obstetrician (OB) regularly, despite presenting with a healthy pregnancy and baby throughout. Seeing a midwife and an OB made Kirryn “feel like [she] had to juggle two opinions”, as there was often obvious tension between the two professions. This made things uncomfortable and frustrating at times. Mama A felt similarly frustrated by her care in hospital, as the model of care was not what she expected. A midwifery model, intended to have continuity of care and focused on familiarity, ended up exposing Mama A to at least seven different midwives throughout her pregnancy, seeing “someone different every week” and eventually an unknown midwife during the actual birth. Luckily, Mama A had a strong support system in her twin sister, mother and grandmother, so she didn’t need to always rely on the midwives to support her.

When deciding on the place to give birth in, it is a smart idea to assess the common risks and benefits of each setting. In hospitals, the risk of intervention is high, and often mothers who decide to follow this path, find themselves experiencing the ‘cascade of interventions’. Many maternity care interventions have unintended consequences which are often “solved” with further intervention. Interventions that are commonly experienced in a hospital setting include labouring in bed (the lithotomy position), artificial rupture of membranes, vaginal examinations, medically inducing labour or extracting the placenta (synthetic oxytocin), stretch and sweeps, performing episiotomies, using forceps or the vacuum, constant electronic foetal monitoring and using medical pain relief (such as an epidural). Often these interventions will interfere with the physiological hormonal response that labour and birth will have, leading to more medical ‘help’ being needed. Such interference can also increase risk of infection and have an impact on the mother’s overall emotional experience, sometimes becoming a catalyst for postpartum depression or post traumatic syndrome. As well as these types of risks, hospital settings can often expose the mother (and family) to feeling pressured, guilty, disempowered or coerced into doing certain things that suit the hospital. For example, in Kirryn’s first birth she expressed a sense of feeling pressured to be induced at 40 weeks. Mama A was given the Syntocinon injection to help synthetically release the placenta after birth, but she remembers feeling angry because it was done without her consent and “recalling [no one] having a discussion about the reason why [she] was receiving the injection”.

Other elements of a hospital that might be perceived as negative, include the physical appearance of the room (bright lights, noisy, clinical, cold, antiseptic smell), the professional power struggle between OB’s and midwives, and the enormous focus on time and routine (e.g. vaginal exams every 2 or 4 hours). I know for me personally; this was something I experienced that impacted my mindset during labour. Frequently my midwife asked me to get up onto the hospital bed so she could perform a vaginal exam to assess my cervical dilation. These examinations were painful and constantly interrupted my labour flow, making me dread each time she had to perform them and instilling anxiety in me for the rest of my labour. For Kirryn, by the time she had birthed her daughter she was on the clock to deliver her placenta. She remembers witnessing her midwife get anxious after an hour had gone by and her placenta still hadn’t appeared, leading the midwife to help manually extract it by pressing on Kirryn’s belly and pulling on the cord (something that can be very dangerous). For Mama A, when she arrived to hospital her and her husband were confronted with “very white, bright lights and lots of equipment around” which abruptly stalled her labour.

Hospitals are often very busy places that frequently have limited staff availability; which can influence a mother’s birth experience. Both Kirryn and Mama A, experienced this in their first births. Kirryn expressed “feeling like an inconvenience” during her overnight stay after the birth. The maternity ward was “extremely busy” and because she had experienced an uncomplicated birth, her calls for help or support were often left unanswered. Similarly, Mama A found herself ignored and alone (in terms of medical staff) during her labour. As a midwife herself, she reflected that the staff probably assumed that she didn’t need any support or assistance as she looked like she was coping and in control. Unfortunately, looking like you’re in control, and actually being in control are two different things.

On the other hand, hospitals can be places of safety and security that allows the mother access to various medical advances and skills. Both Kirryn and Mama A endured perineal tearing from their first births, and therefore had to receive stitches afterwards, a practice that sometimes cannot be performed in a home birth setting. Sometimes, women don’t get the chance to have complete control of where they give birth, such as in high risk pregnancies. Hospitals are arguably the safest place to be in true emergency situations, due to their efficiency, training and access to medical equipment. This often can make women feel like they’ve lost a sense of control. Fortunately, what mothers can control is the look, feel, smell and sound of the space they have been put in. You might not get a say in what colour the walls are in the hospital room assigned to you, but you can bring something from home to cover those walls. There are many ways to make that birth space individual to you. From your favourite music, to essential oils, to salt lamps, to photos of family and affirmation cards, to blankets or pillows from home, and even bringing your own birth ball. Hospitals also give mothers easy access to other services such as physios and lactation consultants to help during her postpartum time. Unfortunately, this sometimes isn’t the case, with Mama A experiencing no medical support for her breastfeeding challenges throughout her stay.

So what made both of these mothers choose a home birth over another hospital birth for their second baby? According to a research paper on Homebirth in WA, the most common reason for women choosing a home birth (in WA) is “avoiding unnecessary intervention.” This is followed by the comfort and familiarity of a home setting and the “freedom to make their own choices”. While the majority of births are done in a hospital setting, only 0.6% of births are done at home in Western Australia according to the Mothers and Babies 2017 report. In Australia as a whole, home birth accounts for only 0.3%2. Kirryn and Mama A both found the transition from home to hospital disruptive and challenging in their first birth. “I hated having to transfer to hospital” exclaimed Kirryn and both mothers reflected that this movement of place stalled or stopped each of their labours. Research shows that labour thrives on familiarity, warmth, darkness and safety – four things that a home setting would bring for most women. Staying at home for both Kirryn and Mama A meant that they could enjoy the comforts of their own space, not have pressures of time, routine or policy, be able to have continuous support available pre and post birth and not “have to deal with the tension between midwives and OB’s” (Kirryn). Women who birth at home often discover a freedom that is lacking in the hospital setting, and as result mothers report feeling more satisfied and empowered by their home birthing experience. Despite this, home birth still gets a bad rap.

With society having such a negative perception of home birth it is hard to believe that birthing in the comfort of your own home was the norm up until the 20th century. Unfortunately, because the history of birth is intrinsically entwined with death, homebirth has far to come in changing its reputation. Sadly, people often forget that the death rate was high for births because of a number of determining factors – not just due to the home setting. Remember, personal hygiene was poor, infection rate was high, medical knowledge was at a minimum and medical technology was non-existent. This is no longer the case in the Western world. And yet “the heart of the homebirth debate [still] rests with the issue of safety in relation to perinatal morbidity and mortality”. As result, women who choose a home birth today, find resistance and judgement from medical staff, family, friends and their community. Kirryn describes getting her home birth signed off by her hospital GP/OB as “not a nice experience”, feeling pressured to agree to certain policies and routines.

Unfortunately, “the wide differences in expert opinion on this subject [of homebirth] create a confusing picture for women”8. For Mama A though, the idea of going back to hospital for her second birth seemed unnecessary and she “felt very drawn to be at home”. Being at home for this birth, meant Mama A could get into rhythm quickly and stay in that zone for the entirety of her labour. “I was so relaxed and coping so well” at home, she exclaimed, “I didn’t need the hustle and bustle” of hospital. Similarly, Kirryn felt completely relaxed “knowing [she] was where [she] needed to be to give birth”. For both women, labouring at home, meant things progressed quickly and easily, experiencing little to no interruptions or interventions. Both women also experienced a physiological third stage, allowing the placenta to come out on its own and having ample amounts of skin to skin time with their newborn baby, which in turn benefited their breastfeeding journeys.

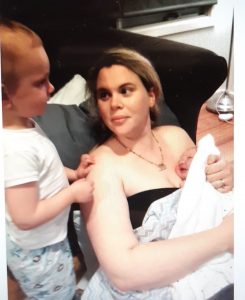

There’s also something so comforting about a homebirth story. In a hospital setting, often women encounter things that are out of their control, such as different staff coming into the labour or various sounds of machines or emergency alarms. During her first birth, Mama A even remembers feeling rushed out of her birth room because the cleaners had arrived to clean. At home though, a mother and her family can relax, take their time, cuddle and even enjoy “tea and toast on the lounge-room floor” after the birth like Mama A did. For Kirryn, one of the most magical parts of her homebirth, was being able to wake her first born daughter up and introduce her to her new sister, an hour after giving birth. “It was such a comfortable, loving environment” she explains. And Mama A describes her homebirth as a time where she “felt listened to” and “felt like [she] had complete control of the situation”.

Obviously both mothers experienced uncomplicated births at home and this ultimately made for a positive and empowering experience. It could be argued that if either of these women had complications during their labour and birth that things might have been perceived differently. Overall though, both mothers described their homebirths as empowering and full of support, love and comfort. These women had considered their hospital experience as not ideal and went in search of something more uniquely suited second time round. Both women would highly recommend homebirth, but both also pointed out that women should inform themselves of the risks and benefits before ultimately choosing their birth setting. “If [women] are willing to put in the time into preparing for birth” Kirryn says, then homebirth could be considered a suitable option.

According to a Finnish study of homebirth women, a positive birth is associated with “perceptions of complete autonomy”, continuous support from a network chosen specifically by the mother and confidence in one’s ability to birth. When a woman feels she has an element of control in her birth then positive outcomes are more likely to follow, “regardless of the place of birth”. So, when deciding on having a birth at home or a birth in a hospital, the question you should be asking instead is:

“Where do I feel like I will have the most support, the safest outcome and the utmost control?”

I want to sincerely thank the two mothers who were willing to share their birth stories with me and for allowing me to pick their brains about their views on birth in hospital and home settings. Thank you to Sara Bresser Photography for sharing these amazing photo’s from Kirryn’s birth as well.

If you would like to read a more detailed account of Kirryn’s homebirth – CLICK HERE

If you would like to contact Sara Bresser Birth Photography – CLICK HERE

My Name is Emma Goodin and I am Your Birth Mama. I’m a doula who has completed extensive training at the Doula Training Academy. If you would like to discuss with me about your birthing options and find out how you can achieve a birth that is calm, connected and confident please feel free to contact me.

Business name: Your Birth Mama

Business email: [email protected]

Phone: 0431 955 932

Website: http://www.yourbirthmama.com

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/yourbirthmama

Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/yourbirthmama

References:

Olsen O, Clausen JA. Planned hospital birth versus planned home birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD000352. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000352.pub2

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019). Australia’s mothers and babies data visualisations. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies-data-visualisations

https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/hospital

Margaret Anderson. (2013) 19th Century Childbirth. Retrieved from http://adelaidia.sa.gov.au/subjects/19th-century-childbirth

Tania McIntosh. (2017). Pushed into it? Retrieved from https://www.historytoday.com/pushed-it

Mary-Rose MacColl. (2008). The Birth Wars. Retrieved from https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/the-birth-wars/

Clare Davison. (2019). Looking Back and Moving Forward: A History and Discussion of Privately Practising Midwives in Western Australia. Retrieved from https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/77506/Davison%20C%202019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Colleen Ball. (2014). Homebirth in WA: Why Women make this choice. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2278&context=theses