A Book Review of “Why Induction Matters” by Rachel Reed of Midwife Thinking

Written by Danielle Bestall

Why Induction Matters; a birth bible written by Rachel Reed for navigating the modern birthing world. Before reading this book, I had been told by at least 5 different people that I needed to get my hands on a copy ASAP. On finishing the first chapter, I knew I would now be joining the Why Induction Matters army and spreading the word near and far. I found myself nodding, saying “oh wow” or “how can women not be told this!” frequently and wanting to inhale all the facts and figures that Rachel presents. Wading through the stats and complex issues of the modern maternity system is not an easy task for pregnant mothers. Rachel Read has succeeded in her quest to produce an easily understood, evidence-based resource that women can refer to, to make an informed decision about induction. It outlines the information about why an induction may be recommended, the process of induction, and the benefits and risks involved with induction.

In chapter 1 – Making Decisions About Induction, I was alarmed to read that situations that are commonplace in our maternity system can by legal definition be considered as assault and battery. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) induction guidelines for health professionals are listed in this chapter. They serve as a great start for women to begin to understand the type of information that their care providers should be sharing when they are being offered an induction. They also offer pregnant women a standard of how they should be treated in regard to their decisions about induction. Rachel explains how the induction of labour came to be a routine intervention and that it is likely to stay this way until there is good-quality research evidence to support a change. It is important to understand the limitations of research into maternity care when taking a closer look at the “evidence-based” care that medical institutions are providing. It is explained that research requires funding and maternity care is not a priority for receiving government-based funding. When government-based funding is taken out of the equation, the only remaining sources of funding are the pharmaceutical and medical technology industries. This leaves little room for unbiased, good quality research into the induction of labour. This is evidenced in the number of Cochrane reviews reporting concerns about the quantity and quality of maternity based studies.

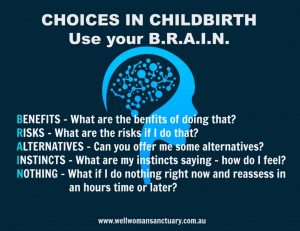

There are notable discrepancies between some of the clinical guidelines listed in this book and the current research-based evidence. The cause of this is noted as the “expert consensus” that is also considered when creating clinical guidelines. This accounts for the lag time seen between new evidence becoming available and a change in clinical guidelines being made. Throughout the chapters, Rachel includes many women’s experiences of induction and this offers the readers a relatable form of evidence to consider. She describes how maternity services assess risk by looking at statistics on short-term, physical and measurable outcomes that impact the organisation. Long term or individual risks are not usually part of the organisations approach to assessing risks. This is important for the individual woman to take into consideration when deciding whether to have an induction or not. I found it so interesting to learn that individuals make decisions based on emotions and feelings which are driven by social and cultural norms. Rachel goes on to say that as well as this, personal experience is one of the most influential factors in decision-making. This made me think about the large number of women that choose to “get informed” and seek out further support in subsequent pregnancies after having a less than positive experience with their first birth. A useful framework is included in this chapter that encourages women to dig deeper into several aspects of induction; the reason that induction is being offered, what the experience of induction will be like, what the alternatives are including their associated benefits and risks. The BRAIN decision making framework is also described and I believe this is a must have for any birthing woman.

In Chapter 2 – Complications of Pregnancy. In this chapter, Rachel breaks down common and not so common complications that can arise during pregnancy. She weighs up fairly the evidence for and against induction in each of these scenarios. These complications include high blood pressure, pre-eclampsia, pre-existing diabetes as well as gestational diabetes, intrahepatic cholestasis, the growth restricted baby, reduced fetal movements, prolonged pre-term rupture of membranes and last but most certainly not least, the death of a baby. Discrepancies in the clinical guidelines are noted for many of these complications, putting even more emphasis on women making informed choices for themselves based on their individual circumstances.

Chapter 3 – Variations of Pregnancy. Rachel makes the difference between a complication of pregnancy and a variation of pregnancy clear at the beginning of this chapter. She states that a variation is where the mother and baby are both well, but the variation increases the risk of a complication occurring. The question then becomes, does the chance of the possible but unlikely complication occurring outweigh the risks of an induction? As a lot of the research focuses on how variations alter the general perinatal death rate, it was beneficial to have the definition of “perinatal death” clarified. It is defined as the death of a baby from 22 weeks gestation until 7 days after birth. Thus meaning that the perinatal death rate includes stillbirth and early infant death. The variations Rachel unpicks in this chapter include; post-dates and post term pregnancy. Rachel breaks this information down into induction for post-dates pregnancies and spontaneous post-dates labour. Referring to the evidence around the variations of advanced maternal age, VBAC, suspected big baby, multiple pregnancy and pre-labour rupture of membranes at term.

In the next chapter – Spontaneous Labour, we are informed about the mysteriously magnificent design of the female reproductive system and when left undisturbed the way that it works to orchestrate a physiological childbirth. We learn that in the final weeks of pregnancy the hormones progesterone, relaxin, beta-endorphins and prolactin begin to prepare the body for birth and mothering. Oxytocin receptors are laid down ready to receive oxytocin from the bloodstream and Braxton Hick’s contractions begin to train the uterus and cervix for labour day. The cervix changing structurally to ‘ripen’ before it opens in response to uterine contractions during labour. It was amazing to read about the bodies of both the mother and baby preparing alongside each other for birth and early life outside the womb, just like the perfect team. The fascinating changes in the brain, fat, lungs and immune system of a baby in the last few weeks of pregnancy are highlighted as so important in their start to life and promote strong reasons not to take induction lightly. Rachel describes wonderfully the roles of the hormones in a physiological labour and birth. She delves into what can either encourage or hinder their progress through both early and established labour, and how they then become responsible for the birth of the placenta as well as early breastfeeding and bonding.

A medical induction of labour can be described in 3 steps – ripening the cervix, breaking of the amniotic sac and creating contractions. In chapter 5, we are informed about the options for ripening of the cervix as well as what the breaking of the amniotic sac involves. The amount of intervention required in an induction depends on a few factors, including how close the woman is to spontaneous labour. It’s noted that most women and in particular those having their first baby will go on from steps 1 and 2 to require a syntocinon drip to create labour contractions. We are told that the cervical ripeness is the first thing to be assessed which then will then determine whether an intervention aimed at ripening the cervix will be required or not. Prostaglandins are described as the star hormone of focus when looking at induction of labour. “All of the interventions aimed at ripening the cervix attempt to either release the body’s own prostaglandins or introduce synthetic prostaglandins.” The methods used to ripen the cervix all have their risks and benefits and the methods discussed in this chapter are membrane sweeping, pharmaceutical prostaglandins and mechanical devices. The breaking of the amniotic sac (ARM) in an induced labour is contrasted against the breaking of the amniotic sac in a spontaneous labour. In an induced labour, the fluid around the baby can prevent induced contractions from getting into an effective pattern as well as reducing the risk of an amniotic fluid embolism. Therefore, this makes an ARM favourable in an induced labour. Whereas in a spontaneous labour it does not speed up labour and can result in unfavourable interventions.

Once the cervix has ripened and the amniotic fluid has been released, the next step in an induction is to create labour contractions. In chapter 6, Rachel covers the use of synthetic oxytocin (Syntocinon) to induce labour contractions. She notes early on in this chapter that an induced labour is generally shorter than a spontaneous labour as the processes of early labour are bypassed. The star of the medical induction show, Syntocinon (Pitocin in the US) is described at length in this chapter. We learn that although it’s chemical make-up is exactly the same as oxytocin and that it acts on oxytocin receptors in the uterine muscle in the same way, there are some big differences in the way that Syntocinon functions in the body. These major differences are listed as; Syntocinon being released into the bloodstream via a drip and the rate remaining unaffected by other factors, that it is unable to cross the mothers blood-brain barrier and acts only on the uterus and it can cross the blood-brain barrier of the baby in very high volumes. All of these important differences have certain consequences. For example, the Syntocinon being administered at a constant rate directly into the bloodstream means that the rate is not naturally altered by feedback mechanisms via information from the uterus, the baby, the mothers emotions and the environment, as is the case in spontaneously occurring labour. The use of Syntocinon in the bloodstream, reduces the release of oxytocin in the brain – therefore affecting the mothers bonding behaviours. The baby’s own oxytocin system and bonding behaviours will also be affected by the large quantities of Syntocinon that cross it’s thin blood-brain barrier. The process of the Syntocinon administration is explained and it was awesome to read that for 50% of induced mothers who chose to have Syntocinon stopped (yes, you have a choice!) once they were in established labour, their own hormones managed to take over and progress onto the 2nd and 3rd stages of labour.

Rachel tells us of the extra interventions commonly required when choosing a medical induction and why each of these are recommended to women. These include an IV cannula, regular vaginal examinations, CTG monitoring and active management of the placenta (a high dose Syntocinon and cord traction). We are also told that women having a medical induction of labour are more likely to require pain relief as they essentially bypass early labour where a steady build-up of beta-endorphins (the body’s natural pain relief) occurs, this is compounded by Syntocinon causing contractions to come at a strong and steady pace without good periods of rest. The potential side-effects and complications of a medically induced labour explored in this chapter are perhaps one of the most important facets of this book. It is these situations that need to be weighed up against the risks of waiting for spontaneous labour by all birthing women that are considering induction. Rachel outlines the potential risks as hyperstimulation, caesarean, malposition of the baby and shoulder dystocia, perineal tearing, neonatal complications at birth, post-partum haemorrhage, water retention, difficulty with establishing breastfeeding, maternal depression and anxiety, and behavioural disorders in childhood.

Rachel then has a look at the evidence or lack of evidence for alternative methods of induction, pointing out that they are still forms of induction as they aim to induce labour before spontaneous labour would naturally happen. What follows is one of the most useful sections of the book – a guide for creating a birth plan for a medical induction. Included is a step by step guide of all the options to be considered in an induction, referring back to all of the information supplied in the previous chapters. It covers essential questions for women to ask their care providers and states how to clearly document their requests in their birth plan.

Today, one in four women will have their labour induced. I feel so strongly that the knowledge contained in this book should be freely accessible to every pregnant woman. I believe we could potentially change our birthing system in Australia “from the bottom up” if we were to hand out a copy of Why Induction Matters at every initial antenatal appointment in Australia.

My name is Danni Bestall and I am a qualified doula who has trained at the Doula Training Academy with Vicki Hobbs.

If you would like to talk more about your birthing options, please contact me:

Business Name: The Birth Flow Co.

Business Email: [email protected]

Phone: 0421 993 639

Facebook Link: https://www.facebook.com/thebirthflowco/

Instagram Link: https://www.instagram.com/thebirthflowco/